What we allow the mark of our suffering to become is in our own hands.

Our lives are shaped and changed by the law; it is the sluice gate through which the river of humanity flows. The law is a slingshot to bring down Goliath.

Rich and poor, weak and strong, all are subject to it and equal before it. With it, any of us can take on a global corporation or a mighty government. And win. It is blind to power and it is blind to identity. Lady Justice atop the Old Bailey does not see who appears before her and no one can put their thumb on the scale she holds because we can always see that justice is done.

At least that is the idea. The reality is more complicated. In England, justice is open to all – like the Ritz Hotel. The law’s tool is too expensive to buy. But that’s not true of everyone. Make any enemy who has money, speak an uncomfortable truth or threaten their interests and you will quickly learn how the law can be used as a weapon to deliver injustice, to bend the weak to the will of the strong.

The hand of a good lawyer holds the mightiest pen. The law should mean justice – but it too rarely does. The law also helps us to engage in the world. Don’t disengage from it and become an acid commentator from the sidelines, rather become a player in the highest stakes game there is.

The life I have had has been hard, but I got to choose it, and the road that brought me here I did not. It seems remarkable now with the distance of the many years since I was 18, that I managed to emerge from this period of my life unbowed. But I also know I grasped and hustled for chances to improve my financial situation. The way I behaved to those around me falls short of the standards that I now, more prosperous, set for myself. But I also understand that ideals of morality are something I can afford now but could not afford then. Sometimes you just survive. Those events have left me with a deep suspicion of ethical standards set by those whose lives have been of unbroken wealth.

The cost of dignity, of the high moral ground, is not fixed. If you are brought up in upper middle England with money and educated at the best public schools, maybe you mediate your expectations to the biggest prizes society has to offer. The stakes are rather higher and the compromises uglier and more demeaning if you are a clueless immigrant.

I survived those years, but I hated and loved them in equal measure. Today they mean I have some ability to imagine my way into the lives of those who lack what I now have. I know that there are some things you cannot learn in books. In real life, poverty and dignity don’t make good bedfellows. Washing backsides and humping potatoes are all well and good, but Victorian ideals of virtue are easier to hold when you rise every morning from a safe and warm bed. The lawyer in me now cannot defend a legal system that criminalises those who steal because they are hungry. That feeling and sentiment has taken me to the path looking out for the underdog.

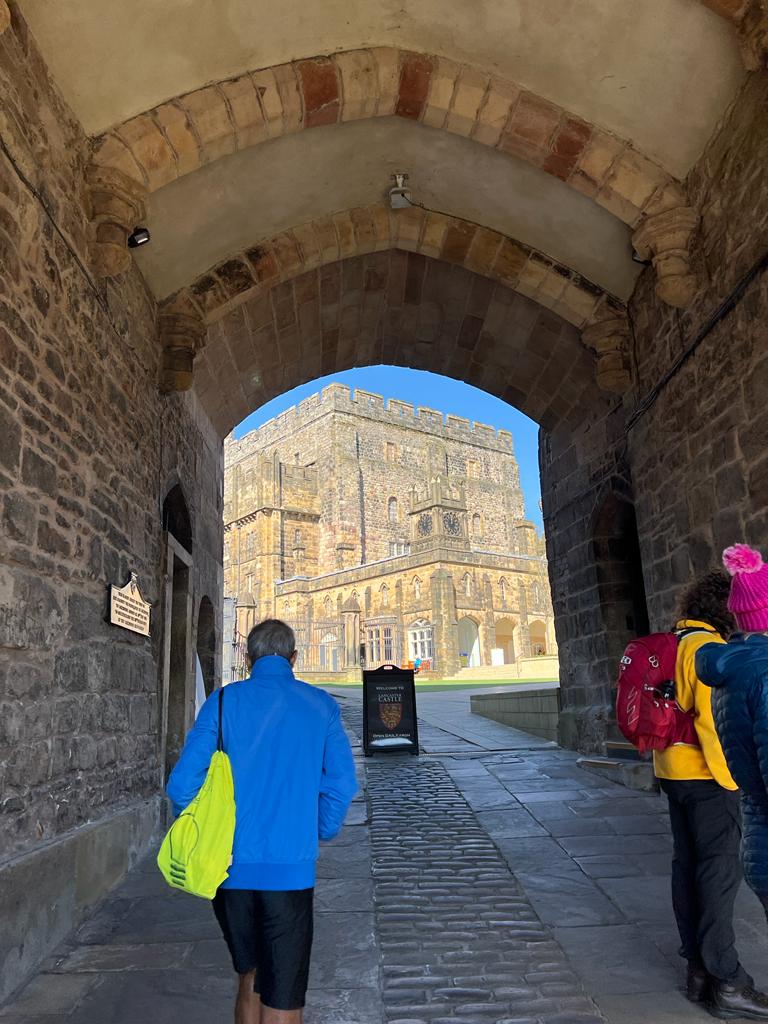

*Lancaster Castle was still functioning as the courts and prison when I began practice. It was here I appeared for my first case in the 1980s following a meeting with my prisoner client. This formidable structure with dungeons and an imposing Gate House dates back to the medieval era. The most famous trial in Lancaster Castle’s history is that of the Pendle Witches. And on a personal note, the Handless Corpse Trial and the Birmingham Six, both of which I was indirectly involved in as I was getting into the law.